Winter parasite control in equines

By Dr Alex Allen BVM&S MRCVS, technical director at Virbac.

RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points.

Parasite control in horses differs over winter from other times of the year. This is due to the lifecycle of the worms and the effect that climatic conditions can have on their development. Winter is the time to think specifically about bots and small strongyles in addition to the year-round threat of tapeworm and roundworms.

Adult large and small strongyles are detected by faecal egg counts (FECs), however FECs do not detect larval stages of bots and small strongyles (also known as Cyathostomins) or tapeworm.

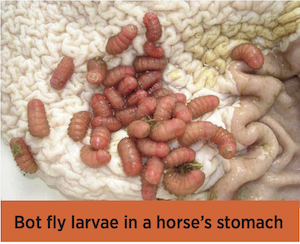

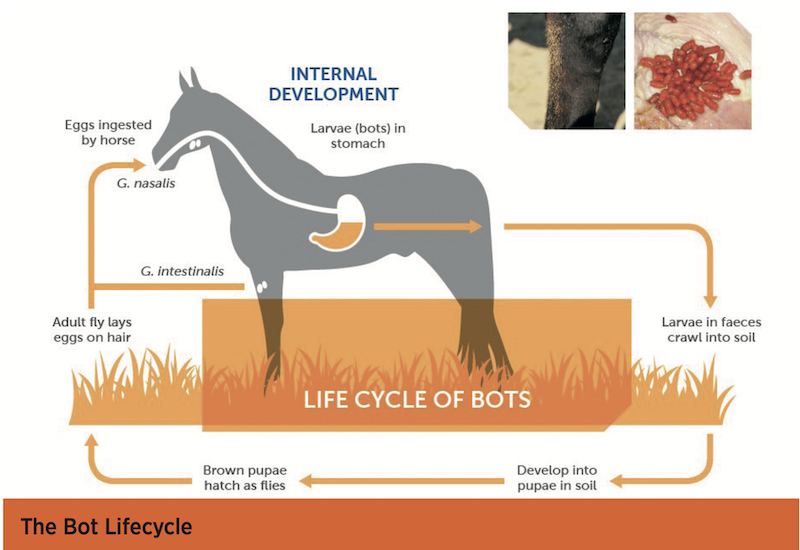

BOTS

Stomach bots are larvae of flies from Gasterophilus species. The flies lay their eggs on the haircoat of the horse in late spring through to the autumn. The horse grooming itself stimulates the eggs to hatch into larvae which are then ingested by the horse.

Eventually the larvae reach the stomach and attach to the stomach lining, where they are frequently seen during gastroscopy. As fly activity ceases after regular frosts, bots over- winter as larvae inside the horse. Worming at this time with an effective wormer such as ivermectin or moxidectin should allow bots to be eliminated, without the chance of reinfection from flies in the environment.

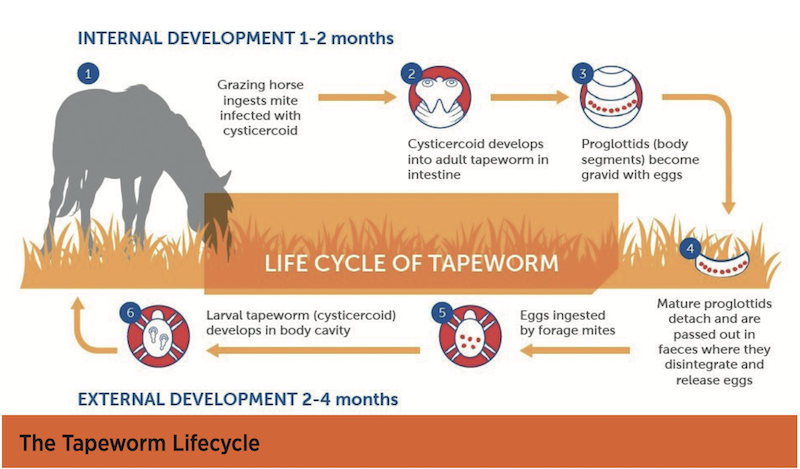

TAPEWORM

Tapeworm have a 6-month lifecycle, therefore horses are traditionally treated for these worms in the spring, prior to the grazing season and again in the autumn. Tapeworm are not reliably detected with faecal egg counts, although tests have recently been developed to measure antibodies to tapeworm to diagnose exposure.

These tests can be performed on saliva or blood samples. If a horse has not been treated or tested for tapeworm in the last 6 months, this should be incorporated into the winter worming regime.

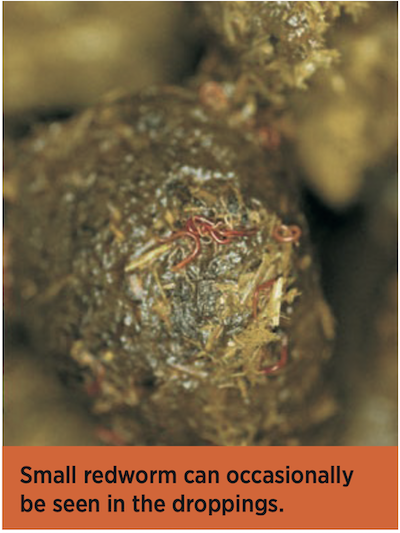

SMALL STRONGYLES

Small strongyle larvae are ingested from the pasture by the horse and some of these larvae undergo arrested development within the wall of the intestines, particularly during the winter months.

The risk of larvae encysting within the intestinal wall is greater in horses grazing heavily infected pastures throughout the year, where there is a high stocking density or short grazing. Encysted larvae can remain in the intestinal wall for 2 years but they often emerge in the spring.

Encysted larvae are a normal part of the lifecycle of the small strongyles, but when large numbers of encysted larvae emerge simultaneously from the intestinal wall, this can lead to intestinal damage and a condition known as larval cyathostominosis. This is characterised by diarrhoea and weight loss. Younger horses less than 5 years of age are most susceptible.

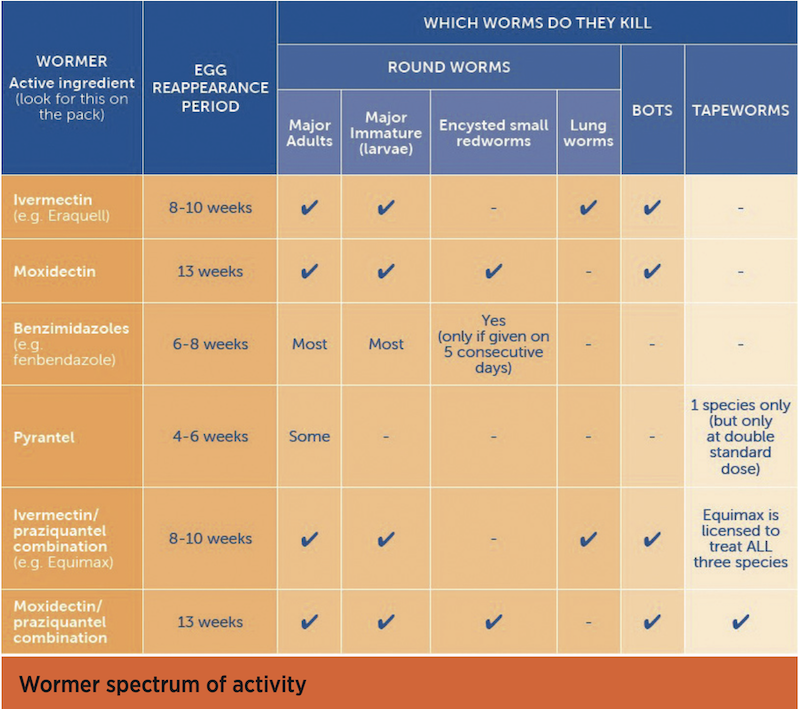

It is recommended that at risk horses receive a treatment for encysted small strongyles once a year. Traditionally this has been performed over winter. Two drugs treat encysted small strongyles, these are moxidectin and fenbendazole.

However, resistance to fenbendazole is widespread. If fenbendazole is used, it is recommended to perform a faecal egg count reduction test to confirm that treatment has been effective.

As moxidectin remains the only effective treatment for encysted strongyles in many areas, many experts recommend that this drug should be reserved for this use and only given once a year to minimise the development of small redworm resistance to this vital product (Coles, 2009). Throughout the rest of the year other wormer drugs should be used.

The colder weather can make it more challenging to maintain good paddock care during the winter months, but it remains important to stay on top of poo-picking and pasture management during this time.

PICK YOUR WEAPON

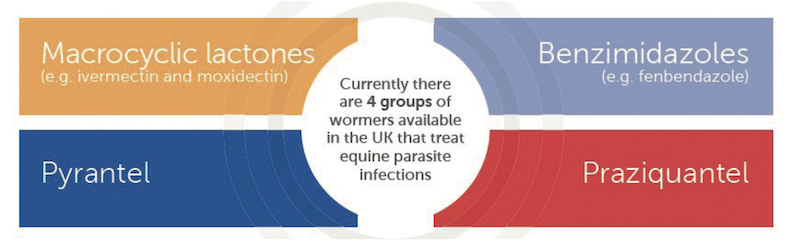

All available horse wormers can be grouped into 4 different classes, according on the type of active ingredient in them that kills the worms. If there is resistance to a wormer in one category, there is a good chance the worms will be resistant to other products in that class too.

This is why, with only 4 classes of wormers available and no new types of wormer on the horizon, it is very important that we do everything we can to maintain their effectiveness and delay the spread of resistance.

Worming becomes complicated because there isn’t one type of wormer that kills all the different worms that infect horses.

Each group of wormer has a different spectrum of activity against different types of worms. This means that when a parasite infection is identified, the appropriate wormer to treat that type of worm must be selected.

Also, not all wormers have equal levels of control, plus some have levels of resistance that compromise their efficacy. This means that despite your best intentions, you may not be protecting the horse from the ill effects of a parasite infection if an inappropriate treatment is used.

As moxidectin is the only effective treatment for encysted small redworm in many areas, using this product sparingly is recommended by experts (Rendle et al., 2019).Develop a structured worming programme for each horse that uses a combination of testing and treatment whilst taking into account the specific parasite threats during the year. Select the right wormer for the specific parasite threat.

Treating different parasites at different times of the year is the key to strategic worming. When it comes to worming, remember the 3D worming approach – Direction, Dosage & Delivery:

Direction

Develop a structured worming programme for each horse that uses a combination of testing and treatment whilst taking into account the specific parasite threats during the year. Select the right wormer for the specific parasite threat.

Dosage

Regardless of the wormer used, ensure that the correct dose is given for the horse’s bodyweight. As bodyweight can fluctuate throughout the year, use a weigh tape or scales to determine this accurately. A winter coat can make visual estimation even harder and most people under rather than over-estimate their horse’s bodyweight, by up to 20% (Asquith et al., 1990). Remember that not all syringes contain the same amount of drug, for larger horses make sure there is enough drug in the syringe.

Delivery

It is imperative that a horse receives the full dose of wormer to be administered. Most wormer syringes contain approximately

a teaspoon of wormer treatment. Therefore any ‘spit-out’ can represent a significant amount of the total dose and will result in under-dosing. This has several consequences; firstly, the product will not work as it should and secondly, it can contribute to the rapid development of resistant worms.

References

- Asquith et al (1990). Erroneous weight estimation of horses. Proceedings of the annual convention of the American Association of equine practitioners. 599-607

- Coles, G. (2009) Anthelmintic resistance in equine worms. Vet Times.

- Rendle et al. (2019). J. Equine De-worming: A consensus on current best practice. UK Vet Equine 3 Suppl 1 3-14.

About the author:

Dr Alex Allen BVM&S MRCVS qualified from Edinburgh University in 1998 before working in clinical practice for several years. He now works for Virbac, a leading animal health company, as technical director. In this role, he oversees and provides technical support to animal health professionals and owners on the use of Virbac products.

ETN’s series of CPD features helps RAMAs (Registered Animal Medicines Advisors/SQPs) earn the CPD (continuing professional development) points they need. The features are accredited by AMTRA, and highlight some of the most important subject areas for RAMAs/SQPs specialising in equine and companion animal medicine.

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its RAMAs/SQPs undertake CPD. All RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming a RAMA/SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk

Horses in snow image by Bee Iyata