Be worm-wise this winter

By Wendy Talbot, national equine veterinary manager at Zoetis.

During the grazing season from February to October, it’s easy for your customers to be guided by faecal worm egg counts (FWECs).¹ They simply need to remember to conduct them every eight to 12 weeks, and then worm according to the results.

No complicated explanations are needed about strategic dosing for those elusive parasites that don’t reveal themselves in FWECs, apart from testing or treating for tapeworm in the spring and autumn.

But with winter on the way, it’s now time to talk about strategic worming that includes treatment for encysted small redworm, tapeworm and bots.

SEEING RED

Small redworm, also known as cyathastomins, are the most prevalent parasite in horses in the UK. They can be found in the horse’s large intestine in the caecum/colon area.²

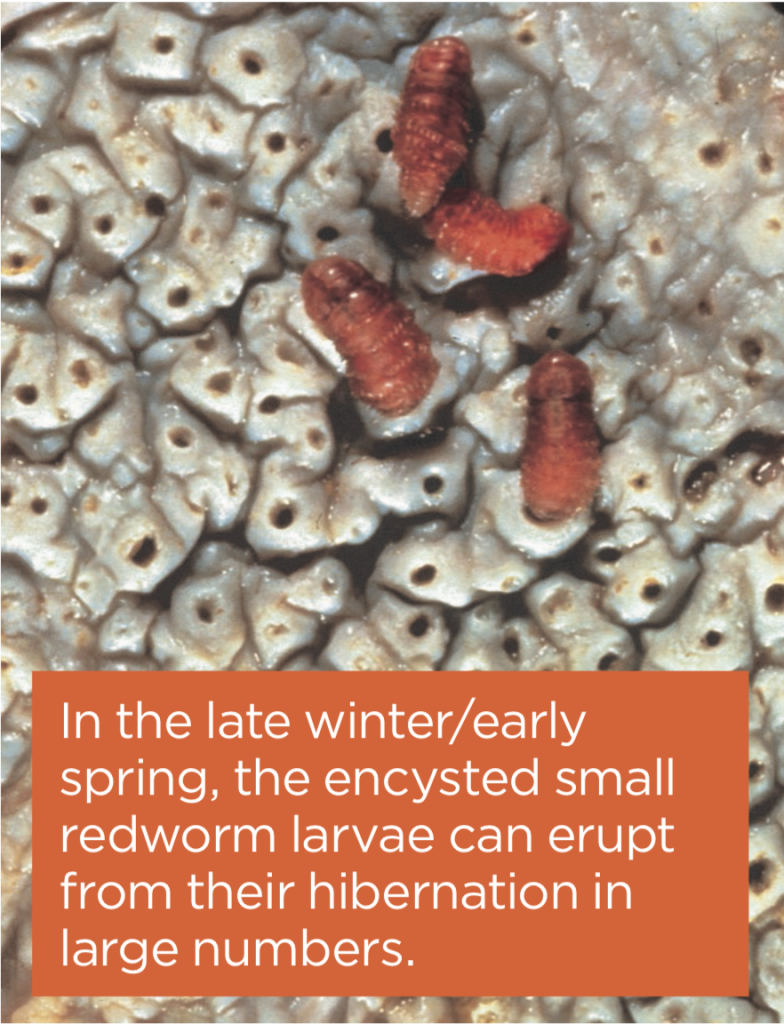

Small redworm are bright red in colour and can range from 1.5-2.5cm in length. The encysted larval stages are the most dangerous and all horses (over approximately six months of age) should be treated during the late autumn/ early winter.³

WHY ARE ENCYSTED SMALL REDWORM

SUCH A PROBLEM?

As a part of their lifecycle, small redworm eggs hatch on the pasture and the larvae emerge. They have to go through three developmental stages before they are able to re-infect horses. Warm wet weather, typical of spring and summer, is optimal for their development and during this time the larval burden on the pasture is high and horses will be continually re-infected by unintentionally ingesting larvae as they graze.⁴

Once ingested, the larvae travel through the digestive system to the large intestine where they burrow into the inner lining of the gut where cyst-like structures form around them. Within the cysts, they can either continue to develop through the larval stages before emerging back into the intestinal lumen, or they can halt development and enter a 'hibernation' state.

The larvae within cysts in the intestinal wall are known as Encysted Small Redworm (ESRW). Hidden here, encysted stages can account for up to 90% of the small redworm burden in a horse. A horse may have several million larvae yet show a negative or low faecal worm egg count.³﹐⁴﹐⁵﹒

DAMAGE CAUSED BY ENCYSTED SMALL REDWORM

Late winter/early spring eruption

In the late winter/early spring, the encysted small redworm larvae can erupt from their hibernation in large numbers, breaking and damaging the lining

of the intestinal wall, which can cause diarrhoea, weight loss and colic. This potentially fatal condition is known as larval cyathostominosis and has a mortality rate of up to 50%. Horses of lessthan five years old tend to be more susceptible.²

Consequences of using the wrong wormer

Treating with a wormerthat does not specificallytarget the encysted stages (ivermectin, pyrantel or single dose fenbendazole) during later autumn and early winter can actually increase the risk of a

horse with a high encysted small redworm burden developing larval cyathostominosis.⁵

THE RIGHT ENCYSTED SMALL REDWORM TREATMENT

There are only two active ingredients effective againstESRW: a single dose of moxidectin or a five-day course of fenbendazole.

Moxidectin has high efficacy against adult small redworm including encysted mucosal larvae. It actually kills the larvae in situ, reducing the inflammation of the gut wall.⁷

There is widespread evidence of resistance in small redworm to fenbendazole, so a Faecal Egg Count reduction test (FECRT or 'resistance test') is recommended before using it.

GET IT TAPED

Tapeworm are transmitted by the forage mite, which is mainly found on pasture. This parasite is a white flat, segmented worm,usually found at the junction of the small and large intestine in horses.

Tapeworm use suckers to attach themselves to the gut wall. They can result in a number of health-related problems, ranging from weight loss to diarrhoea and colic. An infected horse has been shown to be 26times more likely to develop ileal impaction colic than a non-infected horse and eight times more likely to experience spasmodic colic.⁸

In the UK the highest burdens of tapeworm are seen at the end of the grazing season.⁵

THE RIGHT TAPEWORM TREATMENT

To control tapeworm horses should be dosed with praziquantel in a combination wormer or a double dose of pyrantel twice yearly at six-monthly intervals with one of these treatments falling in the autumn to reduce the high burdens acquired during the previous grazing season.⁸

Alternatively, a test can be carried out to establish antibody levels.

BOT OUT

Bots are the insect larvae of the bot fly and are a common adult parasite found within the horse’s stomach. The female botfly can lay up to 1,000 distinctive yellow eggs on the hair of the horse’s legs and shoulders or around the eyes, mouth and nose.

The eggs are accidentally eaten by horses as they groom themselves or a companion. They then develop into larvae inside the horse, usually attaching to the stomach lining.

While bot eggs are easy to identify, bot larvae infection isn’t so obvious. Clinical signs are rare but infection can show as mouth irritation, ulcers or stomach irritation.⁵

THE RIGHT BOT TREATMENT

To control bots, horses need a wormer containing ivermectin or moxidectin, administered in the winter after the first frost when the adult flies have died and before the bots mature.

TOP TIP

Treat all adult horses over the age of six months for encysted small redworm regardless of faecal worm egg count, test or treat for tapeworm and treat for bots at the end of November/beginning of December. A single dose of Equest Pramox will treat for encysted small redworm, tapeworm and bots.⁹

FURTHER LEARNING

For SQPs: Zoetis is committed to supporting learning across the equestrian industry. The company offers a series of Equine Worming Online Continuing Professional Development (CPD) courses for SQPshttps://sqptraining.learnupon.com.

For your customers: Zoetis has produced a sustainable worm control module for The British Horse Society’s Stage 3 Care Award www.bhs.org.uk/ pathways; and an educational website for horse owners www.horsedialog.co. uk contains a wide selection of articles on equine health and wellbeing.

References

- Rendle (2017) De-worming targetedplans. Vet Times, Equine, Vol.3

Issue 1 p16-18 - Love S, Murphy D et al. Pathogenicity of cyathostome infection. Vet Parasitol.1999;85(2-3):113-21;discussion 21-2,215-25

- JB Matthews, An update oncyathostomins: Anthelmintic resistanceand worm control. Equine Vet Educ.(2008)

- AAEP Parasite Control Sub Committee. AAEP Parasite Control Guidelines 2013.

- Reinmeyer CR, and Nielsen MK, Handbook of equine parasite control 2013. Wiley Black

- Dowdall SM, Matthews JB, et al. Antigen-specific lgG(T) responsesin natural and experimental cyathostominae infection in horses.Vet Parasitol. 2002;106(3): 225-42

- Bairden (2006) Vet record 158, 766-768 also add ref. Steinbach for the reduced Inflammation

- CJ Proudman. Diagnosis treatment andPrevention of Tapeworm-associated Colic. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science January 2003 Vol 23 Number 1

- Matthews JB. To worm or not to worm.London Vet Show 2015 (Nov) 157

ETN’s series of CPD features helps SQPs (Suitably Qualified Persons) earn the CPD (continuing professional development) points they need. The features are accredited by AMTRA, and highlight some of the most important subject areas for SQPs specialising in equine and companion animal medicine.

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its SQPs undertake CPD. All SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. SQPs who read the following feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming an SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk