SO, HOW MUCH DO YOU KNOW ABOUT YEAST?

By Hannah Elliott, technical manager at Lallemand Animal Nutrition

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its RAMAs/SQPs undertake CPD. All RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming a RAMA/SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk

Yeast has been in human diets since the ancient Egyptians were using it to leaven bread and ferment wine. Yeast’s exceptional fermentative and nutritional properties make it a valuable and affordable nutrient source for domesticated animals, many of which have been fed some form of yeast for over 100 years.

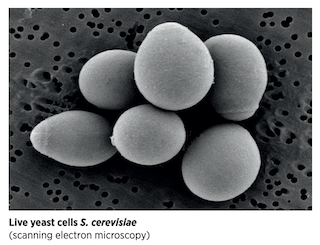

Yeast is a single-cell, eukaryotic microorganism classified in the fungi kingdom. They are around 10μm in size, have a nuclear membrane, a cell wall, and cytoplasmic content. Characterized as heterotrophs, they rely on organic material for energy and nutrients and are very diverse organisms with around 60 genera and 1,500 species, each with unique metabolisms.

Only a few are used commercially, the main species being Saccharomyces cerevisiae, due to its remarkable fermentative capacities and nutritional properties. Annually, S. cerevisiae produces 60 million tonnes of beer, 30 million tonnes of wine, 600,000 tonnes of baker’s yeast and 20 billion litres of bioethanol. Due to its versatility, yeast can also be a product of primary fermentation - specifically and consistently produced for its intended purpose. Or secondary fermentation - the yeast is produced as a by-product of another industry, for example brewer’s yeast, which can result in variable quality and efficacy dependent on its primary use.

Within the Saccharomyces cerevisiae species, there are thousands of strains, each with a unique genetic makeup, leading to different outcomes in composition, metabolism, and functionality when fed to animals. To visualize these differences, the different yeast strains can be likened to horse breeds. A Clydesdale and a Falabella, although both horses with similar physiology, vary greatly in terms of metabolism, characteristics, requirements, and output. Hence, each product should be carefully selected for its desired use and outcome to maximise its efficacy and value.

LIVE YEAST

Four strains of S. cerevisiae are permitted for use as probiotics in horse products within Europe. In general, probiotics help balance digestive microbiota, help reduce undesirable microorganism presence, maintain digestive comfort and support fibre digestion. However, not all live yeast is equal: each strain has an optimum temperature, pH and fermentative capacity both during production and within its host/ application. The S. cerevisiae strains selected for real ale, wine and bread production will be different due to the substrates used, production process, and the required outcome e.g. leavening, alcohol content, desired flavour profile. Similarly, a probiotic yeast may not perform optimally in both ruminants or hind-gut fermenters and monogastric animals due to differences in digestive tract and feed; which is not only supplying our animals with substrates and nutrients, but also feeding and influencing the native microbiota and the probiotics we add. Feeding choices, housing, breed and individual variation in microbiota balance can all effect live yeast efficacy. If you are unhappy with the outcome from one live yeast product, try another. Once you’ve tried one, you haven’t tried them all!

A challenge with probiotic yeast is to ensure the yeast remains alive and active throughout the entire production process, packaging and storage, until it reaches the active site in the animal’s digestive tract. Many different factors can affect probiotic viability such as moisture, temperature, pressure, coating method and other interacting ingredients. To test viability, live yeast can be retrieved from feed and supplements and colonies can be grown and counted in a laboratory to confirm probiotic survival through processing and storage.

“A challenge with probiotic

yeast is to ensure the yeast

remains alive and active

throughout the entire

production process.”

INACTIVATED ENRICHED YEASTS

Yeast can incorporate trace minerals into its cell, making it possible to produce mineral-enriched yeast biomass. Selenium-enriched yeast represents an important source of organic selenium as it offers enhanced selenium digestibility and functionality within an animal. Specific S. cerevisiae strains utilize inorganic selenium, incorporating it into the yeast proteins as organic seleno-amino acids such as selenomethionine and selenocysteine. Yeast naturally contains <10ppm selenium. Selenium yeast products are registered with a minimum guarantee of 2,000ppm total organic selenium and a minimum of 1,260ppm selenomethionine, which serves as an indication of organic selenium incorporation.

To make selenium-enriched yeast, selenium is added to the fermentation medium during fermentation. The incorrect yeast or a mal-adapted process can reduce yield (as selenium reduces normal multiplication and can induce cell death), and result in a Se-enriched yeast product with sodium selenite present (which can damage the gut) and a reduced level of organic selenium. Producing high-quality, concentrated, Se-enriched yeast requires suitable yeast strain selection, specific process development and time.

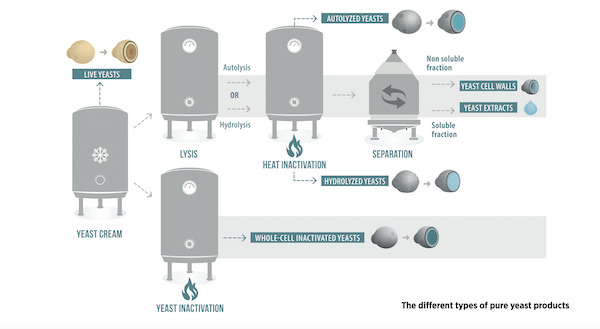

AUTOLYSED AND HYDROLYSED YEASTS

Autolysis is the process of self-digestion, in which the cell is inactivated by its own digestive enzymes (endogenous enzymes) leaving proteins and nucleotides partially fragmented. Hydrolysed yeast are obtained through a further yeast cell digestion by specifically selected exogenous enzymes to obtain the desired level of hydrolysis. The selection of the enzymes, as well as the control of the conditions, will determine the product composition, consistency and functionality. Hydrolysed yeast still contains the cell wall and yeast extract as there is no separation step during the process and so offer both nutritional and functional advantages such as palatability with the presence of highly digestible proteins, free amino acids and nucleic acids, as well as insoluble components.

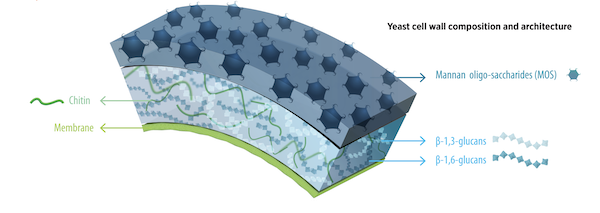

YEAST CELL WALLS

Yeast cell walls (YCW) are the insoluble fraction of autolysed or hydrolysed yeast, obtained after the separation from the cytoplasmic content (yeast extract). The YCW represents 30-40% of the dry weight and consists of two layers. Each YCW product and strain has a specific composition and cell structure, such as the number and density of adhesion sites, which directly influences its functionality and application in animal nutrition.

- The external layer is rich in mannan oligo-saccharides (MOS) and represents 20-30% of the YCW depending on processing conditions. MOS are responsible for binding flagellated undesirable bacteria, for parietal exchanges, porosity/permeability and, more widely, the protection of the yeast from the environment. The main role of MOS products within animal nutrition is binding capacity, helping to limit the development of undesirable bacteria within the gastrointestinal tract and ensure an optimal intestinal integrity. Favouring the development of beneficial microorganisms within the intestinal microbiota gives a prebiotic effect. The effect is strongly dependent on the inclusion rate, mannan length and its adhesion capacity.

- An additional step can be applied during the YCW production to remove the MOS layer via enzymatic or chemical treatment to obtain a product containing a high level of exposed ß-glucans for specific immune system modulation function. The percentage of ß-glucan and MOS should be measured during the quality control step of yeast production to ensure consistency.

- The internal layer, rich in β-1,3 and β-1,6-glucans (representing 20-35% of the YCW), provides rigidity and flexibility to the cell wall. β-glucans modulate the innate immune system of animals, which helps reinforce their natural defences. It also contains chitin (≈2% of the YCW), which has a major role in the integrity of the cell wall, affecting the “cohesion” of the wall.

CONCLUSION

Yeast is an adaptable and valuable source of functional and nutritional components for horses. Each yeast product has its own characteristics and beneficial effects on digestion, well-being and health, especially in stressful situations. Numerous yeast products are available creating a plethora of options and often a misconception that a lot of yeast and yeast products are the same. It is essential to understand the differences between yeast products, their production processes and strain to make a cost effective decision and select the most appropriate one for their desired effects based on specification and functionality when added to feed or supplements.

ABOUT ETN’S RAMA/SQP FEATURES

ETN’s series of CPD features helps RAMAs (Registered Animal Medicines Advisors/SQPs) earn the CPD (continuing professional development) points they need. The features are accredited by AMTRA, and highlight some of the most important subject areas for RAMAs/ SQPs specialising in equine and companion animal medicine.

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its RAMAs/SQPs undertake CPD. All RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming a RAMA/SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk