Feeding for performance

By Anna Welch BVSc, BSc, MORCVS. Veterinary Nutrition Director, TopSpec.

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its RAMAs/SQPs undertake CPD. All RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming a RAMA/SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk

Optimising a horse’s diet will help them to achieve their maximum potential whatever discipline they are being asked to perform in.

Understanding a performance horse’s need for energy, protein, micronutrients, and water, as well as effective ways of supplying them, will allow you to offer the best advice to your customers.

Energy

Carbohydrates are the main energy (calorie) source for horses and can be divided into two forms: -

(1) Structural Carbohydrates

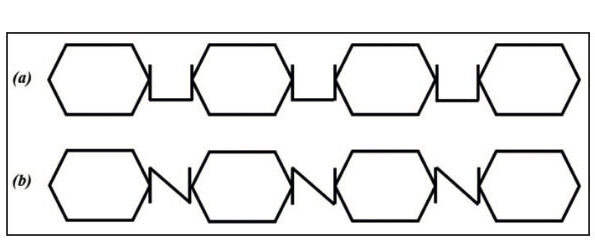

Structural carbohydrates occur in the cell wall portion of the plant and are referred to as fibre. In contrast to non-structural carbohydrates (see below), the sugar units are bound by β-linkages (Figure 1) which cannot be broken down by enzymes in

the horse’s small intestine. Therefore, fibre passes to the large intestine (hindgut) where it is fermented by the microbes (largely cellulolytic/fibre-digesting bacteria) that reside there.

This microbial fermentation produces the short chain fatty acids acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which can be used by the horse as energy. This fermentation of fibre is a continual process that is crucial to both the function and efficiency of every horse’s digestive system, and to their overall health and performance.

Dietary fibre also holds water in the hindgut, though its water holding capacity depends on the fibre types and maturity. This fluid reservoir is important for hydration and can be drawn upon during times of increased demand.

(2) Non-Structural Carbohydrates

Non-Structural Carbohydrates (NSCs) include sugar and starch. The sugar

units that make up NSCs are bound by α-linkages which can be broken down

by enzymes, such as amylase, in the

small intestine of the horse to produce glucose. Glucose is then absorbed into the bloodstream and transported to various tissues in the body, where it can either

be used to provide energy immediately or stored as glycogen or fat. Glycogen is stored in the muscles or liver, where it can be utilised as fuel at a later time as required.

However, amylase is only produced in small quantities by the horse and therefore, horses are limited in the amount of starch they can digest at a time. If large quantities of starch are fed, excess undigested starch passes into the hindgut where it is digested by acid producing bacteria, including amylolytic (starch-digesting) bacteria. Consequently, numbers of these bacteria increase, and the hindgut becomes more acidic, causing microbial imbalance, which can result in several problems for the horse (including loose droppings, colic, ‘tying-up’, laminitis, and irritable or sharp behaviour).

Fat / oil

Fats and oils are known as lipids. They are a source and store of energy, are important components of cell membranes, transport fat-soluble vitamins and are integral to many other bodily functions.

Triglycerides are the most common lipid type in a horse’s diet, and these are broken down in the small intestine to produce fatty acids which are absorbed. Whilst the horse’s digestive system has not evolved to metabolise a high fat diet, it can be utilised very effectively and brings certain benefits.

Oil is very nutrient-dense and supplies over twice the energy as an equivalent amount of starch (from e.g. cereal grains such as oats). This makes oil an excellent way of helping to keep meal sizes small and supplying additional calories without the need for higher starch and sugar ingredients. When used correctly, oil can also have a ‘glycogen sparing’ effect and delay the onset of fatigue.

Which energy type?

Whilst all horses should receive ample fibre, which is a ‘continually releasing’ energy source, there may need to be an emphasis on further fuel types depending on the individual and the exercise performed.

Highly strung horses and those prone to certain nutritionally-related issues such as gastric ulcers, loose droppings, colic, laminitis, tying-up, and stereotypical behaviour, can benefit from a low NSC but high fibre and oil diet.

Horses participating in endurance exercise, which is largely aerobic (‘with oxygen’) rely more on oil alongside fibre. Shorter duration and more intense exercise, which is largely anaerobic (‘without oxygen’) utilises glycogen reserves and the ‘faster-releasing’ energy of starch/sugar. However, there is always a combination of both aerobic and anaerobic metabolism.

Protein

Protein is the second major constituent of all tissues in a horse’s body, second only to water. Protein is not an ideal energy source, but it has many important functions, including providing structure (e.g. in muscle, bone, cartilage, hooves, and skin), metabolic functions (e.g. enzymes and hormones), the immune system (e.g. antibodies), and nutrient transport (e.g. haemoglobin and albumin in the blood).

Proteins consist of amino acids that are linked together with peptide bonds. The sequence of amino acids is unique to each protein. All 22 amino acids are needed for protein synthesis but there are 10 that a horse cannot make himself, so they must be supplied by the diet. These are called essential amino acids and lysine is the most limiting for a horse.

Micronutrients

Vitamins, minerals, and trace elements have many different physiological functions that are essential to health and performance. Horses in hard work will have greater requirements for these micronutrients compared to those in little or no work.

There is a significant requirement for vitamin E and selenium (antioxidants) with exercise, as these have an important role in muscle metabolism. The demand for vitamin E and selenium is further increased by high oil diets.

Vitamin C is another antioxidant, which can help to maintain healthy airways and, alongside vitamins A, D and E plus Mannan Oligosaccharides (MOS), support the immune system.

Vitamins A and D also have roles in bone metabolism, with calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, copper, zinc, and manganese. Good bone strength and remodelling is essential to a performance horse.

Certain vitamins (including B vitamins) and trace elements are essential for energy metabolism. Hard working horses are also more likely to have compromised hindgut function, so their own supply of B vitamins will be diminished.

Working horses lose a significant amount of sodium, chloride, and potassium in their sweat, plus traces of calcium, magnesium, and phosphate. For optimum performance and recovery, these losses should be replaced appropriately using salt (sodium and chloride) and/or electrolytes.

Many trace elements have a multitude of functions in the horse’s body, in addition to those mentioned above. Their importance is not reflected by the low intake required.

Levels of micronutrients should be carefully considered and balanced correctly with each other. Over-supply can be toxic in some cases or limit the absorption of other micronutrients.

Water

A mature horse’s body consists of approximately 65% water, and it has many vital functions including hydration, body temperature regulation, and the transport of nutrients and removal of waste.

In a 24-hour period, a 500kg horse could drink between 25 and 50 litres of water; this intake will depend on their diet, level of work and the environmental temperature.

Putting theory into practice Forage

Most horses should be offered forage (hay, haylage, grass or chops) ad-lib and it is beneficial for as much of their energy/calorie needs as possible to be met by forage, as this will reduce hard feed requirements.

When grass quality is good, it is sensible to make the most of the grass available. Maximising turnout may also be beneficial for horses who can be sharp, although some can be sensitive to high-sugar grass in spring.

When horses are stabled or travelling, conserved forage will be necessary. It makes sense to feed a performance horse good quality hay or haylage (e.g. early cut hay or haylage) but, for those needing a low sugar diet, a lower nutritional value forage may be necessary (e.g. late cut meadow hay).

Good doers

When grass, hay and/or haylage supplies ample protein and calories, a top specification non-conditioning feed balancer or multi-supplement designed for performance horses is the best way of supplying micronutrients without excessive weight gain. These horses are usually unable to consume the recommended amount of compound feed whilst maintaining ideal condition.

A salt lick should be available 24/7, with salt added to the daily feeds as these good doers will receive little salt from their limited diet. Commercial electrolytes should also be included for 2 to 3 days after significant sweating.

Horses with higher requirements (e.g. those working very hard and/or poor doers)

A horse with higher calorie and protein requirements will need more from their hard feeds but it is important that their maximum meal size (e.g. 2kg for a 500kg horse) is not exceeded.

A top specification conditioning feed balancer will enable the horse to utilise maximum nutrients from their forage, so will help to keep meal sizes small whilst supporting condition and performance. The addition of an appropriate blend, straights or compound feed will provide further protein and calories as required.

For the best muscle development (as well as muscle function and repair) high quality sources of protein (with high levels of all 10 of the essential amino acids) should be used. Soya is the best quality vegetable protein source for horses and linseed is the second best.

Products containing highly digestible fibre sources (‘super-fibres’, such as sugar beet pulp and soya hulls) and oil should be used when Digestible Energy (DE) requirements are high, but a low NSC diet is needed. It takes time for a horse to adapt to utilising oil effectively: so, introduce gradually over a period of 6 to 12 weeks, by which time it should be utilised effectively.

When higher starch diets are necessary, it is important to feed cereal grains that are digested well in the horse’s small intestine. The cereal grain with the best pre-caecal digestion rate in horses is oats.

Horses fed on straights like oats will still need their diet supplementing with salt. However, if they are fed sufficient blends or compounds (e.g. 3 to 4kg per day for a 500kg horse) further salt might be unnecessary as they are already balanced for salt. It will depend on the level of sweat produced. Electrolytes would also be required for 2 to 3 days after significant sweating.

Horses with additional needs

Whilst all horses should always have access to ample, clean, fresh water, if they don’t drink well a mash (or other appetisers such as apple juice) can be used to encourage fluid intake.

Certain feed can be used to supply additional beneficial ingredients for horses with sensitive stomachs, such as β-glucans, pectin, and long-acting buffers.

Pre and probiotics can help to support the normal hindgut microbial balance which is likely to be affected by hard work. Fussy horses, or those that become fussy with increased fitness, can also benefit from being supplemented with vitamin B12 (which can help to stimulate appetite), alongside appetising flavours such as mint and peppermint.

Nutraceutical joint supplements, that provide the veterinary recommended level of glucosamine (10g/500kg horse/ day) and MSM, could also be considered as most performance horses will be subject to increased forces upon their joints.

Monitoring the diet

A horse’s condition will reflect whether they are receiving an appropriate level of calories/energy, and protein, so this should be monitored, and the diet fine- tuned accordingly. The enthusiasm with which a horse approaches their work, their ability to sustain their performance and recover well, can indicate whether they are receiving the right energy sources for them. However, many factors are involved and if poor performance

is an issue, a full evaluation of the diet should be carried out; whilst the natural ability and temperament of the horse, their fitness and any health issues are also considered.

It is best to speak to an experienced nutritionist to tailor this general advice to individual circumstances.

ABOUT ETN’S RAMA/SQP FEATURES

ETN’s series of CPD features helps RAMAs (Registered Animal Medicines Advisors/SQPs) earn the CPD (continuing professional development) points they need. The features are accredited by AMTRA, and highlight some of the most important subject areas for RAMAs/ SQPs specialising in equine and companion animal medicine.

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its RAMAs/SQPs undertake CPD. All RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming a RAMA/SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk