What do we mean by sustainable parasite control?

Targeted worm control to take care of our horses and the environment, by Claire Shand of Westgate Laboratories.

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its RAMAs/SQPs undertake CPD. All RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming a RAMA/SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk

sustainability

Noun

Meeting the needs of the present without

compromising the ability of future generations to

meet their own needs.

When we talk about sustainability, even sustainable parasite control, this definition from the United Nations sums it up perfectly for me. And although I don’t want to start off on a downer, by this measure we are currently failing both our horses and the environment.

Concern about the overuse of worming chemicals in animals has never been higher. Treatment, where it has been reckless, is causing rapid resistance problems; while a burgeoning area of research is revealing the devastating effects they can wreak on our environment too.

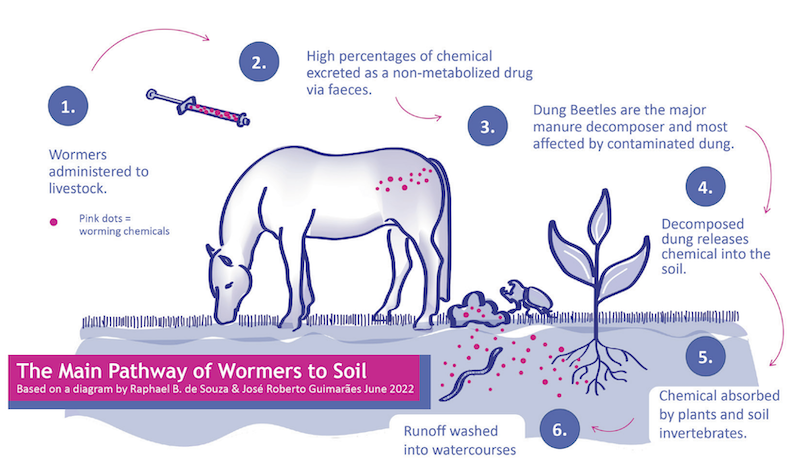

Following use, toxic levels of these chemicals are passed out in the dung, crippling soil ecosystems and in particular harming our ‘first responders’ the dung beetle populations and other micro flora and fauna which form the basis of the food chains in our ecosystems. Turn on any nature programme and we quickly learn of the devastating decline of many of our native wildlife species in the British countryside. Much of that starts with the chemicals we put in and on to our domesticated animals, the products of which have terrible unintended consequences in the environment around us.

Poo picking

Research shows that the single best way to reduce chemical contamination AND our reliance on them is to poo pick regularly – this breaks the lifecycle of the parasites by removing the eggs from the pasture before they hatch. But fresh dung is also essential habitat for our dung beetles, little critters that could play an important role in helping us to manage animal waste naturally, negating the need for all that heavy labour and giving a host of added benefits to the land, if we let them. It might seem counterintuitive at the outset but if we can manage our grazing to reduce parasite infection and preserve habitat for dung beetles there are wins all round for horse health and the environment.

- Start by making sure the parasite control programme is working. Worm egg counts conducted every 8-12 weeks, combined with six monthly to yearly tapeworm testing, will form the basis of horse’s programme. Base the intervals on the relative risk profile of the horse(s) to enable you to identify any problems in the herd and allow any wormy individuals to be treated accordingly. Avoid blanket treatments so there is always some non-toxic dung available to dung beetles. You may need to worm more often and poo pick with greater frequency in the beginning to reduce infection levels.

- Small redworm eggs laid in dung take around a week in optimal UK conditions to hatch and develop into motile L3 larvae. Research therefore suggests that poo picking twice a week is sufficient to significantly reduce infective larvae on the pasture. Dung beetles prefer fresher animal poo up to 48hrs old. Begin to leave the newest piles on the pasture and clear them after 3-4 days.

Minimise chemical contamination

Of our five licenced wormers for horses, ivermectin is the most toxic to dung beetles and moxidectin moderately toxic while pyrantel, fenbendazole and praziquantel are thought to be significantly less impactful in the environment. I was shocked to discover that between 80 to 98% of an oral dose of ivermectin passes straight through the horse and is excreted in the dung without being metabolised by the body. Once in the environment it’s also one of the most resilient chemicals, persisting at high concentrations in faeces for many weeks leaching into the soil to be absorbed by plants and invertebrates and washed into watercourses, often with lethal effects. This doesn’t mean avoiding these chemicals – we still need to use the right chemical for the job. Ivermectin, for example, is an excellent wormer for targeting adult stages of small redworm through the grazing season when an infection has been identified. But it does mean being aware of it’s potential environmental impact and advising on ways to mitigate it doing the same job out in the environment that it is doing in our horses.

- Testing first reduces selection pressure by targeting treatments and helps us to select the right chemical, so protecting key medicines. Where treatment is necessary, ensure sufficient wormer is given for the weight of the horse. Recommend administering on a surfaced area so that any spill can be monitored for dosage and cleaned up to prevent it getting into the ground. Add in reduction testing at least annually – a second worm egg count conducted 10-14 days after treatment – to monitor for resistance.

- Once the wormer is given, minimise the horse’s time on the pasture for up to 10 days and poo pick at least daily during this time. The more eco-toxic the chemical you’re using, the more diligent you should be. This will limit chemical toxins getting into the environment and reduce incidences of tapeworm reinfection for the horse.

Wormers licenced for tapeworm treatment (praziquantel and pyrantel) cause packets of tapeworm eggs to be released in the dung which can trigger a surge of eggs onto the pasture in the first few hours after treatment. Most chemicals reach their highest concentration in faeces 24-34 hours after being administered. If you can only stable for a short time, advice is to keep horse in for 24hrs the day following worming to mitigate both these effects. That means if you gave the wormer at 3pm on Saturday, for example, the horse should be stabled from Sunday afternoon until Monday afternoon. It may also help to restrict treated horses to a smaller paddock for 10 days to aid dung collection.

- Where possible, worm when dung beetles are less active between November and February

Managing contaminated dung

- Dung that you’ve collected from treated horses can be placed in a carefully situated manure pile and allowed to rot down. Although dung beetles will be attracted to muck heaps, they generally don't breed in them. Research has shown thermophilic composting (where the centre of the pile reaches a min 60 °C) will cause even ivermectin, one of the most resilient worming compounds, to break down almost entirely in around 5-6 weeks.

- The siting of muckheaps should be carefully considered. The main environmental risk comes from the impact of residues in rainwater runoff leaching into soils and watercourses. They should be positioned at least 3m outside of fields to prevent hatching larvae re-contaminating grazing land, away from areas where there is a lot of surface groundwater, field drains and not within 10 metres of a watercourse. In an ideal world cover your muck heap with a roof/tarp to reduce the risk of run-off.

- Manure should not be spread back on the land for at least 6 months (ideally longer). By then concentrations of parasiticides should be low and worm eggs will be much reduced tominimise reinfection, particularly where small redworm are concerned. The eggs of the ascarid parasite have a hard, sticky outer shell that is much more resilient, and their eggs can survive for up to 10 years in soil. Studs and breeding facilities should therefore be much more judicious about disposal of collected dung.

Benefits of cultivating your dung beetle population

Dung beetles really are nature’s waste disposal teams; they clear-up large quantities of animal faeces by tunnelling and breeding within dung, feeding upon it and burying it below ground. Or they would if we let them flourish instead of systematically poisoning them with routine chemical wormer doses. We have over 60 species of dung beetle native to the UK but numbers have been in massive decline since the 1960s when routine use of wormers was first introduced.

Horses can produce around 3-5% of their body weight in dung every day. For an average 16hh horse that’s around 18kg of dung a day or 6.5 tons every year! If we spend half an hour poopicking every day, that is over 182 hours a year on removing dung from our pastures.

Their action also fertilises and aerates soils, improving its ability to retain water and increasing nutrient availability to plants - beneficial for both root structures and other organisms. Entomologist, Dr Sarah Beynon suggests they contribute up to £367 million in ecosystem services. They could save us even more time and money if we looked after them better!

Importantly the activity of the dung beetles is also thought to break the parasite life cycle by removing the dung medium that acts as the incubator for the parasite eggs. This prevents the worm eggs hatching into motile larvae which would otherwise wriggle away from the dung and climb the grass stalks to re-infect the grazing horses.

Like all conservation projects, dung beetle populations will take time to recover and be greatly influenced by the surroundings outside your fields too. But take heart, there are many benefits to making the effort. Some beetle species will fly in from up to 10 miles away for the right poo!

So, a little bit of strategic thinking to look after these insects will pay huge dividends to our time, our horse’s health and the environment in the long run. An investment worth making for all our sakes and another angle we can use to encourage horse owners to test first and target treatment.

ABOUT ETN’S RAMA/SQP FEATURES

ETN’s series of CPD features helps RAMAs (Registered Animal Medicines Advisors/SQPs) earn the CPD (continuing professional development) points they need. The features are accredited by AMTRA, and highlight some of the most important subject areas for RAMAs/SQPs specialising in equine and companion animal medicine.

AMTRA is required by the Veterinary Medicines Regulations to ensure its RAMAs/SQPs undertake CPD. All RAMAs/SQPs must earn a certain number of CPD points in a given period of time in order to retain their qualification. RAMAs/SQPs who read this feature and submit correct answers to the questions below will receive two CPD points. For more about AMTRA and becoming a RAMA/SQP, visit www.amtra.org.uk